There are occasionally English voices calling for the ejection of Scotland and/or Ulster from our United Kingdom—probably not seriously in most cases, simply people letting off steam after listening to the latest deliberately irritating antics of the SNP. But insofar as some are serious, what vested interest have the English in the preservation of the Union?

Historically, England has won many battles against the French—Crecy, La Roche-Derrien, Poitiers, Agincourt, to name but some. Those battles were won despite English kings having to leave forces behind in the north to guard against opportunistic incursions by Scots. E.g. 1346, when a Scottish army marched south to eventual defeat at the Battle of Neville’s Cross; given what Edward III achieved with his curtailed forces, imagine what he might have achieved if he could have taken not only his northern armies with him, but a Scottish army too. The Angevin Empire might exist yet—and stretch to the Rhine (or the Volga).[1]

If the lost opportunities of the past are not recognised, similar opportunities in the future risk being lost as well.

For centuries, English and Scottish kings tried to nullify the respective threats from their borders; this was to some extent achieved with the amicable relations established between Scotland’s James VI and England’s Elizabeth I. The shortcoming of convivial relations between leaders of separate countries is that the cordiality cannot be guaranteed to outlast the leaders themselves. Uniting the two countries obviates that issue.

An independent England today need have no worries about invading Scottish armies, but it would have to worry about a hostile SNP-run state.[2] A state that would seize every opportunity to act against England’s interests (just as the Republic of Ireland has proved a poor friend[3]) and cause mischief as part of any international institution it is allowed to join—one more vote against England in the UN, etc. Perhaps Sturgeon will even do a Merkel and invite the 3rd World in, many of whom will then flow south.

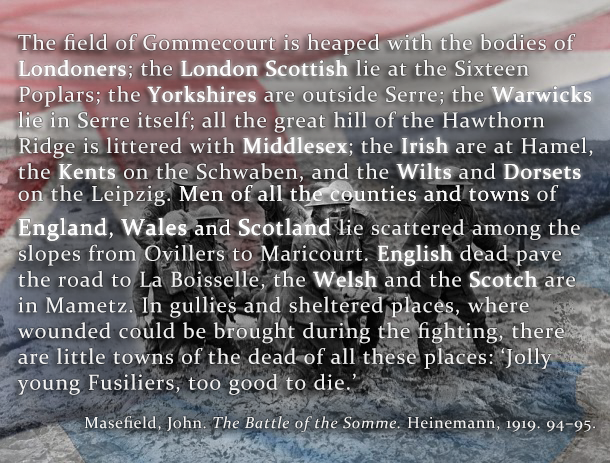

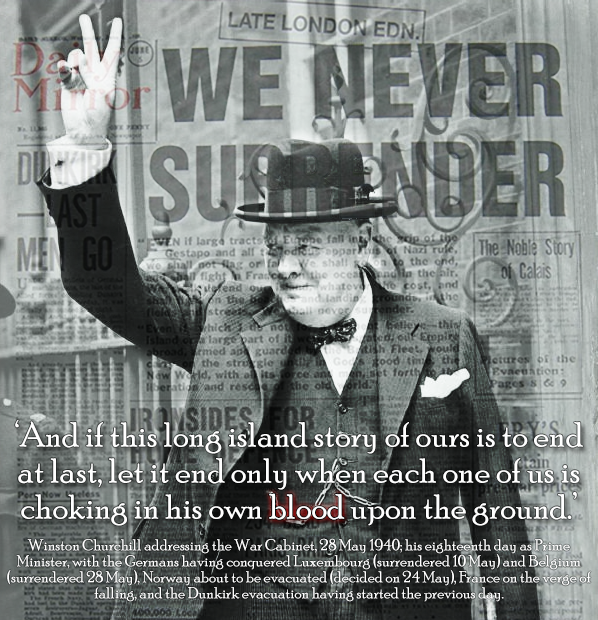

That since 1603 we are an island nation—a superb natural obstacle to any invader—is a rare advantage[4] and one of our greatest assets. E.g. at Corunna and Walcheren in 1809 and Dunkirk in 1940: instead of a defeated army run into the ground, our lads were evacuated to recover and fight again. If we had not been an island, Buonaparte or Hitler would have rolled right over us, just as they rolled over every other nation except for Russia (her advantage being her immense space). Instead, we recovered most of our forces, and from the security of our island, were able to reassess what we were doing wrong, resolve, reinforce and re-equip, then go back at a time and place of our choosing. Not only today but for the foreseeable future, our surrounding seas and English Channel are a massive obstacle against any would-be invader;[5] and while there are currently no obvious potential invaders, no-one can know what the geopolitical situation will be in 100 years or 50 years or even in 10 years. (No-one anticipated WW1 becoming the slaughterhouse and destroyer of empires that it did, even in June 1914.[6])

Currently, the main threat to our borders is illegal immigrants. Again, our island affords us natural advantages: we need only ensure adequate coastal defences, which can be reduced as they go further north (no immigrants are rowing across the North Sea to the Orkneys). Unless an independent Scotland agrees similar immigration policies, a reduced England would be forced to the expense of building, maintaining and manning a substantial border barrier in addition to coastal defences. Certainly well within the resources of a reduced England—but why bother when all is needed is to maintain or augment existing coastal patrols and airport controls the cost of which can be shared?

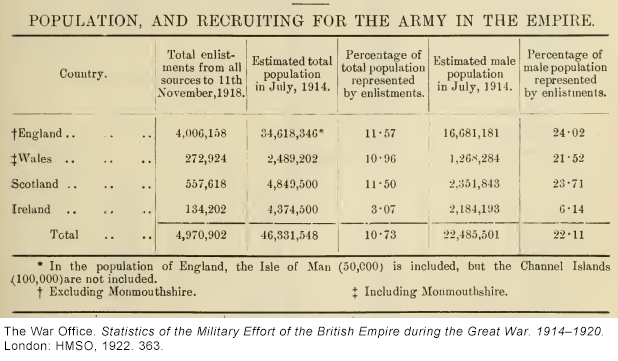

The British military was weakened by southern Ireland’s departure. Whereas in WW1, Ireland provided (without conscription) 206,000 servicemen,[7] in WW2 this was reduced to less than half (38,000 volunteered from NI and 43,000 from RoI). Our war against the U-boats was hampered by the loss of Ireland’s Atlantic ports—and airfields on Ireland’s west coast would have substantially improved the range and loiter time of our Coastal Command aircraft. Ireland gave us one of our greatest generals with Wellington[8]—who knows what other military genius we are missing with RoI gone? The loss of Scotland will not break the English military but it will weaken it, even more than the loss of southern Ireland: unlike Ireland/Northern Ireland where it was deemed too politically sensitive to introduce conscription in either war or National Service post-war, there has never been a problem with conscription in Scotland—a decent reserve of manpower, if needed.[9]

It is often difficult to find any achievement or sacrifice, success or failure, that is wholly Scottish or English or anything else; it is nearly always a joint effort to some degree. For a random example, Al Murray in one of his Pub Landlord routines: ‘You say Bannockburn, I say Culloden.’ Despite his Oxford history degree and historical knowledge, he is wrong in thinking Culloden a counterpart to Bannockburn: it was the final battle of a British civil war, a dynastic struggle, with Scots, English (with enough English Jacobites to form a ‘Manchester Regiment’) and Irish on both sides (something of a Scottish civil war, many of the Scots fighting for Hannover being the Protestant, more urbanised Lowlanders versus the rural, Roman Highlanders). Or there is one of Britain’s—if not the world’s—most remarkable political philosophers, John Stuart Mill, born in London to a Scottish father and English mother. Arguing over whether Mill is Scottish or English is a hiding to nothing. As Aristotle wrote, ‘The whole is greater than the sum of its parts’.[10]

There is also the loss of prestige that a reduced England would suffer. We weathered the loss of Southern Ireland—as far as the world was concerned, we had just defeated three major world powers (Germany, Austro-Hungary and the Ottomans), considerably expanded our Empire (at German and Ottoman expense), and Ireland was not granted complete independence but rather dominion status, and it could reasonably be presumed the Irish Free State would become as loyal as the Union of South Africa had, despite the bitter war we had fought against the Boers. But there are no such distractions now: a reduced England would stand disgraced before the world, a nation unable to maintain its own territory and borders—in the face of a majority of the surrendered territory’s inhabitants being loyal and even its disloyal minority being entirely passive, not exploding a single bomb or firing a single bullet or even throwing a single brick. (N.b. One of the factors contributing to Argentina’s invasion of the Falklands in 1982 was the announced withdrawal of HMS Endurance, as this was thought to portend a lack of commitment to defending the islands. If withdrawing a ship armed with only two 20mm cannon can cause a war, what would surrendering loyal territory without a shot being fired do?)[11]

Only defeated countries cede territory: thus France ceded Alsace-Lorraine after losing the Franco–Prussian War; and Austria-Hungary was split up and Germany ceded territory after they lost WW1; and Germany ceded still more territory after losing WW2; and the USSR disintegrated with the collapse of Soviet authority after losing the Cold War. Has Britain lost a war?

Furthermore, the proliferation of small, weak nations carved out of the defeated empires of WW1 were little more than causes of international tension and triggers for war, being too weak to defend themselves and ensnaring larger nations in their problems. Czechoslovakia, for example: they enjoyed 20 years as an ‘independent’ nation desperately pursuing alliances with other countries before being occupied by the Nazis for 6 years then run by the Reds for 44; two years after communism’s collapse, the Czechs—as if not already weak enough—decided to split further, and now rank amongst the smallest voices in the EU. They would have been better staying part of Austria-Hungary—as would the rest of the world, as Adolf would have not touched the Sudetenland if it had remained Austro-Hungarian.[12]

One can also reasonably wonder how long an independent England would remain intact. As Soviet dissident Igor Shafarevich observed: ‘Why is it thought that different peoples cannot live within the bounds of a single state of their own free will and to the benefit of all? If they cannot, surely one is entitled to doubt that different individuals can do so.[13] Already there are calls from Cornwall,[14] Yorkshire,[15] Wessex[16] and now London[17] for devolution and/or independence. Scotland becoming independent will only encourage and strengthen the various separatist movements.[18]

Finally, there are constitutional consequences arising from the loss of Scotland: the Act of Union (Ireland) 1800 that united Ireland with Great Britain is the legal basis for Northern Ireland being part of the United Kingdom. While the Act of Union 1707 united the parliaments of England and Scotland, the Act of Union 1800 united the parliaments of Great Britain and Ireland; if Great Britain ceases to exist, the Act of Union 1800 ceases to have effect, and Northern Ireland would de jure, if not de facto, no longer be under British rule. That will matter little to English separatists, some of whom make common cause with Irish Republicans; but few patriots will easily see Northern Ireland lost, and the deaths of over 720 British servicemen and women wasted.

The majority of ordinary English are as steadfast and loyal as ever;[19] but it is disturbing that there are increasingly vocal separatist elements in England[20] (as with Scotland, their vocalness is in inverse proportion to their numbers), and even amongst the political elite, e.g. journalists Simon Heffer[21] and Peter Hitchens,[22] author Roger Scruton,[23] EU fanatics like A.C. Grayling,[24] and career politicians who would make short-term political advantage of gerrymandered constituency boundaries in England to ensure Conservative Party success to the long-term detriment of the nation.

Separatism only leaves both old and new nations weaker, and transforms troublesome regions that can be stamped on into sovereign nations that international law demands respecting. No sane person demands their country become smaller and weaker, while creating or recreating potential adversaries. In 1900 an Irishman, Canuck, Aussie or Brit could speak and the world trembled as they had the might of Empire behind them; now, who cares? Divided, we’re weak; united, we could be a superpower. It is as much to the advantage of the English as it is to the Scots and Welsh[25] that our island remain united as one nation. It’s our island: fight for it—work for it.

Endnotes

[1] As Daniel Defoe wrote in 1706:

It would be too tedious here to recite the innumerable Instances, how the Divisions of these Nations have assisted to the rising Glory of our Neighbours; and he that has not read how France, under Charles the Dauphin, afterwards Charles the VIIth. when by the Conquest of Henry the Vth. she was almost entirely subjected to the English, recovered her self, chiefly by the Valour and Assistance of the Scots, must not pass with me for a Historian.

Had Scotland been then united to England, and the Thirty Thousand Scots, which at sundry Times went over to assist that dejected Prince, been sent thither to joyn the English Armies, then under the brave Duke of Bedford, Regent of France, and the best Generals England ever saw, France had, for ought we know, been entirely subjected to the English Power, and Britain had given Law to all these Parts of the World.

’Twould be endless to trace Antiquity, and bring upon the Stage the very many Instances when Scotland has had the Fate of England in her Hand; and again, when England has put the Yoke upon the Neck of the Scots Power. The only useful Observation from which, to the present purpose, is, How these alternate Advantages over one another, have tended to the weakening both; and, by a Chain of Disasters, has helpt to reduce us both to the present Condition, and Danger of being overpower’d by our too potent Neighbours; who, had these Nations been long ago united under prudent and politick Measures had perhaps been always kept too low to have lookt us in the Face.

(Defoe, Daniel. An Essay at Removing National Prejudices against a Union with Scotland. London: 1706. 3–4.)

[2] The SNP, as they showed with rigging the electorate as far as they could get away with for the 2014 Referendum, would do their utmost to contrive any constitution of an independent Scotland to ensure their nearly perpetual rule.

[3] The Irish Government under de Valera reneged on the 1921 Anglo–Irish Treaty, defaulting on loan repayments, causing the Anglo–Irish Trade War (1932–38). They provocatively laid claim to sovereign British territory in their 1937 constitution, a claim that remains in 1998’s Nineteenth Amendment although less provocatively worded (despite such irredentism conflicting with the founding principles of the United Nations that Ireland joined in 1955, as described in General Assembly resolution 1514 (XV) of 14 December 1960: ‘Any attempt aimed at the partial or total disruption of the national unity and the territorial integrity of a country is incompatible with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations.’). Ireland’s WW2 policy of strict neutrality saw them intern Allied servicemen alongside Axis personnel (and after the war they blacklisted their citizens who had selflessly gone to Britain to serve, but welcomed fleeing Nazis; and to this day, Dublin is host to a statue of Nazi collaborator Séan Russell). Later Irish Governments contemplated invading Northern Ireland in 1969–70 and 1986; attempted to arm nationalists in Northern Ireland; and interfered with Britain’s fight against IRA terrorism by dragging us to the ECHR in The Republic of Ireland v The United Kingdom: ECHR 18 Jan 1978, and refusing to employ internment (unlike de Valera), agree meaningful cross-border security cooperation or extradite IRA terrorists. Despite us helping to bail the RoI out(*) in 2010 and agreeing to defend their airspace(†), their government asked the ECHR to reopen the aforementioned case in 2014. Later the then-Irish Taoiseach Enda Kenny backed charging UK for leaving the EU; while current Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, cleaving to the EU, has done his utmost to undermine Brexit. Varadkar, on 20 October 2018, crowed about Ireland paying back IMF loans early and how they have a ‘Rainy Day Fund’, sneering about helping Britain out ‘financially in the future if they need it for some reason…’—blithely ignoring they’ve still to even start paying back the £3.2bn loaned them 2010–13, on which they’re currently paying interest only (latest report to 31 Mar 2019 here). (* ‘Bilateral loan to Ireland: legislation and credit facility agreement’ documents (HM Treasury); ‘Bilateral loan to Ireland’ collection (HM Treasury)) († ‘RAF to defend Ireland in event of air terror.’ Irish Examiner, 8 Aug 2016.)

[4] Of the world’s current 195 nations, less than a quarter (47) are ‘island nations’, of which only Japan is significant.

[5] The Lockheed C5M SuperGalaxy, of which the USAF has 52, can carry two 61-tonne Abrams main battle tanks, while the Boeing C17 Globemaster can carry one. Impressive—however, e.g., the US 1st Armored Division has 159 Abrams MBTs, along with 173 Bradley MICVs, 36 M109 155mm SPGs, 18 MLRSs, 30 Avenger air defence systems, plus 49 helicopters; an armoured division cannot feasibly be deployed by air—at least not into contested airspace. (1st Armored Division Association. 1st Armored Division: WWII & Beyond: the History, the Stories, the People. Turner, 2005. 19.)

[6] Two days before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and 39 days before Britain’s declaration of war on Germany, Kaiser Wilhelm’s health was being toasted by Royal Naval officers on his visit to the British fleet at Kiel.

[7] 134,202 for army alone: War Office. Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War, 1914–1920. 1922. 363.

[8] Wellington has long been calumnied with having said about his Irish birth, ‘just because you are born in a stable does not make you a horse’. This is false, being actually said by Irish nationalist agitator Daniel O’Connell: ‘When the witness came to the portion of the speech in which Mr. O’Connell spoke … The following passage in reference to the Duke of Wellington was received with great laughter: “The poor old Duke! what shall I say of him, To be sure he was born in Ireland, but being born in a stable does not make a man a horse.” ’ (Testimony of Frederick Bond Hughes in Shaw’s Authenticated Report of the Irish State Trials. Dublin: 1844. 93. Online.) In contrast, Arthur Wellesley, as Member for Trim, in 1792 in his first address to the Irish Parliament, said, ‘In regard to what has been recommended in the Speech from the Throne respecting our Catholic fellow subjects I cannot repress the expression of approbation on that head. I have no doubt of the loyalty of the Catholics of this country, and I trust that, when the question shall be brought forward respecting this description of men, we will lay aside all animosities, and act with moderation and dignity, and not with the fury and violence of partisans.’ (The Speeches of the Duke of Wellington in Parliament. Collected and arranged by the late Colonel Gurwood, C.B., K.C.T.S. In Two Volumes. London: 1854. 1–2.)

[9] The War Office’s 1922 Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War contains the following table:

As percentages of both total and male populations, Scottish recruitment to the army compares favourably to that of England and Wales (marginally worse than England with 0.07%/0.31% fewer and slightly better than Wales with 0.54%/2.19% more). Ireland, however, provided noticeably fewer to the war effort in terms of percentages of available population.

Note that the English figure will include recruitment to units such as the London Scottish, London Irish Rifles, Liverpool Scottish, Liverpool Irish, Tyneside Scottish and Tyneside Irish.

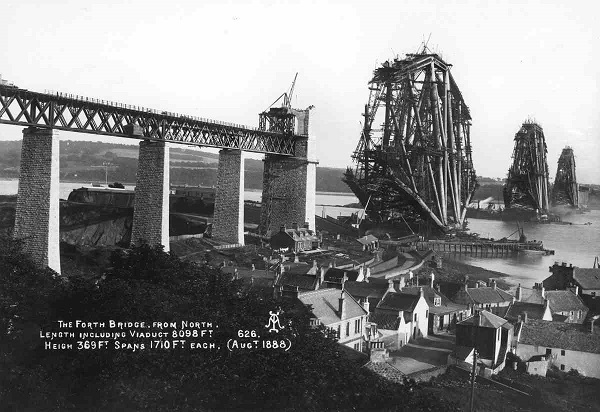

[10] As a further example, there is that iconic model of Victorian engineering, the Forth Bridge.

‘When I journeyed up to Scotland a few days ago, travelling on the Highland Express over that magnificent structure, the Forth Bridge, that monument to Scottish engineering and Scottish muscle …’

Richard Hannay, delivering an impromptu address to a Scottish audience. (The 39 Steps. Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, performances by Robert Donat and Madeleine Carroll, Gaumont, 1935.)

Fine words, and no harm in them; but not really true. The Forth Bridge, was initiated by the North British Railway, who formed the Forth Bridge Railway Company to build it—this being composed of the North British Railway, along with England’s Midland Railway, North Eastern Railway and Great Northern Railway. Its design was by Yorkshireman John Fowler and Somersetian Benjamin Baker. Construction was headed by Englishmen Sir Thomas Tancred and Joseph Philips, Irishman Travers Falkiner and the Scottish Sir William Arrol; the actual construction work was carried out by mainly Scots and Irish.

Even our famous local regiments tended to have a smattering of ‘foreigners’—Scots in English regiments, English in Scottish, etc. E.g. Here is Lt Col H.U.H. Thorne of the Royal Berkshire Regiment who ‘won distinction in command of the 12th Royal Scots, and was killed in the Battle of Arras, April 9th, 1917, leading the first wave of assault “in the old chivalrous way,” as his Brigadier wrote’ (Cruttwell, C.R.M.F. The War Service of the 1/4 Royal Berkshire Regiment (T.F.). Oxford, 1922. 47.). E.g. the famous Welsh victory at Rorke’s Drift was not quite that Welsh: ‘Of the 122 soldiers of the 24th Regiment [later titled the ‘South Wales Borderers’] present at the Battle of Rorke’s Drift, 49 are known to have been of English nationality, 32 were Welsh, 16 were Irish, 1 was a Scot, and 3 were born overseas. The nationalities of the remaining 21 are unknown.’ (Holme, Norman. The Noble 24th: Biographical Records of the 24th Regiment in the Zulu War and the South African Campaigns. Savannah, 1999. 383.)

That said, how ‘foreign’ were these various ‘foreigners’? How did Norman Holme define nationality? Were his ’49 … of English nationality’ actually English, or merely born there of Welsh parents? Such questions, of human interest but minor consequence to Britons, assume otherwise unmerited importance when separatists deny the contributions of brother nations.

[11] Were English separatists somehow able to achieve their goal, it would be an extraordinary act of pusillanimity. Note that even today it is common to joke about a supposed French propensity to surrender (here (2017) is the old chestnut, ‘WW2 French Army Rifle for Sale. Never fired. Only dropped once.’)—appallingly unjust after an estimated 90,000 French died fighting for France in 1940. Many things went wrong for the French, from doctrine to missed opportunities and poor decisions by their generals; but while the French government, and perhaps some generals, could be accused of lacking moral fibre, there is no cause to doubt the bravery of the ordinary poilu. Contrast France’s situation then with English separatists now: no Jerry panzers heading for our capital—no war at all; instead, an established loyal majority of residents and a disloyal but passive minority, their most violent act being to smash some Tunnock’s Teacakes. For English separatists to hand over Scotland to such a passive minority would be a historically unprecedented act of cowardice.

[12] Soviet dissident Igor Shafarevich (1923–2017) identified the problem with small nations:

Recent decades, it is true, have shown a tendency toward the formation of ever smaller states, but this by no means proves that this trend is correct. The small and minuscule states that have appeared in recent times are too weak: they are doomed in all possible respects to become dependents and hangers-on of larger states. They can acquire power only by acting together, subordinating their individuality to a common purpose, and always choosing the course of action that will offend nobody in other words, the most trivial.

(Shafarevich, Igor. “Separation or Reconciliation?—The Nationalities Question in the USSR.” From Under the Rubble, edited by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Gateway Editions, 1974, pp. 88–104.)

Author Lewis Grassic Gibbon(1901–35)—claimed to be amongst Sturgeon’s favourite authors—put it admirably and more colourfully:

About Small Nations. What a curse to the earth are small nations! Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Finland, San Salvador, Luxembourg, Manchukuo, the Irish Free State. There are many more: there is an appalling number of disgusting little stretches of the globe claimed, occupied and infected by groupings of babbling little morons—babbling militant on the subjects (unendingly) of their exclusive cultures, their exclusive languages, their national souls, their national genius, their unique achievements in throat-cutting in this and that abominable little squabble in the past. Mangy little curs a-yap above their minute hoardings of shrivelled bones, they cease from their yelpings at the passers-by only in such intervals as they devote to their civil-war flea-hunts. Of all the accursed progeny of World War, surely the worst was this dwarf mongrel-litter. The South Irish of the middle class were never pleasant persons: since they obtained their Free State the belch of their pride in the accents of their unhygienic patois has given the unfortunate Irish Channel the seeming of a cess-pool. Having blamed their misfortunes on England for centuries, they achieved independence and promptly found themselves incapable of securing that independence by the obvious and necessary operation—social revolution. Instead: revival of Gaelic, bewildering an unhappy world with uncouth spellings and titles and postage-stamps; revival of the blood feud; revival of the decayed literary cultus which (like most products of the Kelt) was an abomination even while actually alive and but poor manure when it died… Or Finland—Communist-murdering Finland—ruled by German Generals and the Central European Foundries, boasting of its ragged population the return of its ancient literary culture like a senile octogenarian boasting the coming of second childhood…

(Gibbon, Lewis Grassic. “Glasgow.” (1934) Smeddum: A Lewis Grassic Gibbon Anthology, edited by Valentina Bold, Canongate, 2001, pp. 97–109.)

[13] Shafarevich, Igor. “Separation or Reconciliation?—The Nationalities Question in the USSR.” From Under the Rubble, edited by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Gateway Editions, 1974, pp. 88–104.

[14] ‘Mebyon Kernow … a progressive left-of-centre party in Cornwall … is leading the campaign for the creation of a National Assembly for Cornwall …’

Campaign for a Cornish Assembly

‘Graffiti has appeared in Falmouth at the entrance to the Old Hill estate calling for a “free Cornwall” as well as on the railway bridge over Arch Hill in Truro.’ (“Condemnation for ‘An Gof’ vandalism.” Falmouth Packet, 25 Apr 2007.)

‘This week, a shadowy militant group calling itself the Cornish National Liberation Army allegedly threatened these two celebrity chefs in Cornwall, suggesting that their presence is not welcome.’ (Hicks, Nigel. “Cornish independence is back on the menu.” Daily Telegraph, 15 Jun 2007.)

[15] ‘The Yorkshire Party is a progressive political party … We call for a Yorkshire Assembly (with real powers similar to Scotland) …’

‘The Yorkshire Devolution Movement … set up in 2012 to campaign for a directly elected regional parliament for Yorkshire.’

‘Brexit, Catalonia, Scotland… Yorkshire? “God’s own county” is pushing for devolved independence.’

[16] ‘The Wessex Regionalists—the party for Wessex … are a progressive, party believing in social, economic and environmental justice. We campaign for a minimum of devolution for Wessex, with the same powers passed to a Wessex Assembly as those devolved to Scotland.’

[17] “Petition for London independence signed by thousands after Brexit vote.” BBC, 24 Jun 2016.

[18] ‘[T]he Free North Campaign … want the North of England to become an independent socialist republic where economic and political power is decentralised to a regional, community, industry and workplace level.’ Note also how the assorted separatist movements inspire and promote each other.

[19] Defoe, Daniel. Ibid. 2.

I believe I may be allow’d to say, without any Charge of Partiality, or Affectation to our selves, or of our real Merit, That there are not Two braver Nations in the World; or that have more shown their Courage and Gallantry, upon all Occasions, than the English and the Scots.

[20] And separatism is sometimes desired over nonsensical issues: e.g. the Daily Express trumpeted a Question Time audience member impatient at Brexit’s delay, who said: ‘If Ireland is the problem, give it back to the Irish. Let them have it. They don’t want to be part of us anyway. I don’t care, I just want out of this damn mess.’

1) The NI–RoI border issue is irrelevant to Brexit, and that it is an issue at all is due to HMG’s incompetence at best, or a mendacious attempt to subvert the 2016 referendum result at worst. We tolerated a far ‘harder’ border than any so far envisaged for decades due to the security situation in NI—the sky fell not; the world continued to turn. We. Coped. An honest and competent government would have no difficulty in leaving the EU without ceding sovereign British territory and it is preposterous that anyone should contemplate such a notion.

2) That ‘[t]they don’t want to be part of us anyway’ would be news to this lot, and these residents, and whoever painted this, along with the 398,921 voters who voted for explicitly Unionist parties in the 2017 GE (only 32.1% of Ulster’s electorate but greater than the 26.9% who voted for explicitly separatist). Out of the 3,620 security-related deaths since 1969 to date (May ’19), 3,400 have occurred in NI itself; of the 2,126 people murdered by Irish republicans, at least 62% have been Northern Irish; the RUC/PSNI have recorded 38,157 shooting incidents, and 3,075 bombing incidents involving 17,036 devices, and to February 2012, recorded 50,600 people injured. No-one has suffered more than the Ulster people themselves; that anyone should dismiss all that suffering—some of it specifically English (the majority of the 722 servicemen killed would have been English, and England suffered the Birmingham, M74 and Warrington bombings amongst others)—is little short of disgraceful (but as already noted, English separatists have form for sympathising with Irish republicanism).

3) Ulstermen were with us at Blenheim, at Lexington and Concord, at Badajoz and Salamanca, at Sevastopol, South Africa, and the Somme; they landed with us at Anzio, fought with us at Monte Cassino and marched with us through France and Germany; they’ve been beside us in every conflict we have ever fought. They are our brothers, as British as our Welsh brothers, our Scottish brothers, our Cornish brothers, our Geordie brothers, our Yorkshire brothers: they bought our loyalty in the blood of generations; and paraphrasing Good Queen Bess, we should think foul scorn of any who would dare surrender a corner of our realm.

[21] Heffer writes that ‘in the early 1990s … I detected a movement in Scotland that would demand Home Rule’. Given that the SNP were founded in 1934, won their first seat in 1967 and had previously (and wrongly) thought to have been on the cusp of victory when gaining 30.45% of the vote (22.78% of the electorate) in the October 1974 General Election, Heffer could not be said to have his finger on the pulse of Scottish politics. He continues: ‘One reason I regard Gladstone as one of our greatest leaders is that he realised … the impossibility of coercing Ireland … and since the notion of English troops enforcing the Union on the streets of Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen was unthinkable, it occurred to me that they had better have [Home Rule].’ With Irish separatists killing and planting bombs in England from the 19th Century onwards (Manchester policeman murdered in 1867; 1867 Clerkenwell Bombing; The Fenian Dynamite campaign 1881–85), and bombing Coventry before Göring did, it is absurd to compare the Irish issue with the Scottish, who have been quiescent since 1746 (and even then more Jocks fought for Hanover than for Stuart). However much the current batch of separatists embarrass Scotland, they remain a minority, albeit a substantial one, and limit themselves to mainly verbal abuse (the worst physical act they have done is throw water at people). And in the face of this fairly pathetic minority, Heffer wants to throw in the towel. Cowardice, thy name is English separatism.

Furthermore, our military are subject to the same Common Law obligations as all other British subjects to act in aid of the Civil Power when called upon (see “Operations in the UK: The Defence Contribution to Resilience.” Joint Doctrine Publications 02 (2nd Edition), Sep. 2007.) Having a fit of the vapours at the prospect of a few squaddies on our streets is risible. While putting troops on Scotland’s streets is ‘unthinkable’ to Heffer, we have done so before without the skies falling, and our nation remains intact.

With regard to Ireland, although the 1918 election notoriously saw Ireland’s electoral map painted green, examining the election results in detail is revealing: Irish separatists obtained votes from only 36.27% of the electorate, with almost half of Ireland’s electorate not voting. If we had held a referendum on Irish independence—presenting the Irish electorate, as the Scots were in 2014, with a single question of remaining with or separating from Britain, divorced from party baggage and long manifestoes, and where every vote counted—we almost certainly would have won if requiring a ‘supermajority’ to vote for independence; and could well have won on a simple majority of vote cast. We let down many loyal Irish by leaving as we did.

Irish separatists obtained votes from only 36.27% of the electorate, with almost half of Ireland’s electorate not voting. If we had held a referendum on Irish independence—presenting the Irish electorate, as the Scots were in 2014, with a single question of remaining with or separating from Britain, divorced from party baggage and long manifestoes, and where every vote counted—we almost certainly would have won if requiring a ‘supermajority’ to vote for independence; and could well have won on a simple majority of vote cast. We let down many loyal Irish by leaving as we did.

[22] While loyal Scots were singing ‘Rule Britannia’ in George Square in celebration of their victory, Hitchens was penning a craven act of surrender to surpass Chamberlain’s ‘Peace in our time’, writing after the loyal vote proved otherwise: ‘If the Scots want to go, as they may well’. Demonstrating historical ignorance, he closes with, ‘I think we should make it clear that they would always be welcome back, and leave a light burning in the window’—as if any country in the history of the world that has become independent has ever asked to return to former rulers (the new nation’s Political Class ensures that never happens). In 2021, he returned to the topic, even as the SNP was beginning to disintegrate without the external help from Westminster that should have been its priority: ‘I can see no way of stopping Scotland from leaving the Union’—well, not if you won’t attempt even the most paltry effort at resisting and promote their cause (‘PETER HITCHENS: Say goodbye Scotland, put Wales on our flag—and let’s save England!’) even as they disintegrate all by themselves.

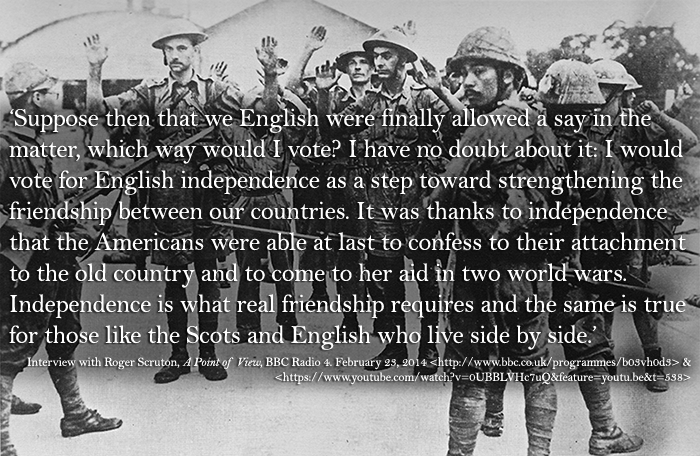

[23] Link is to a February 2014 interview on BBC Radio 4, where Scruton declared (in a remarkably passionless voice, sounding as if he can’t decide what kind of tea to order):

Separation ‘strengthening the friendship between our countries’? It is fortunate he never became a marriage counsellor: ‘The only way to save your marriage is to divorce.’ Had he ever descended from academe’s ivory towers to enlist, he might have coined that infamous line: ‘We had to destroy the village in order to save it.’ As for, ‘It was thanks to independence that the Americans were able at last to confess to their attachment to the old country …’, he seems ignorant of the War of 1812 (and the many loyal Americans who did not need to treasonously rebel against King and mother country and kill loyal English, Welsh, Scots, Irish and fellow Americans to ‘confess to their attachment’ to it only to wait 131 years before actually doing anything—they were fighting for it). Since the 1783 Treaty of Paris ended hostilities between the American rebels and Britain, the new nation was in a virtual Cold War with Britain until ‘The Great Rapprochement’ at the end of the 19th Century. The Treaty of Paris was no sooner signed than reneged on:

11. A full compliance with the terms of the Treaty of Paris would have required the American government to pay the nation’s outstanding prewar debts to British merchants, and the separate state governments needed either to restore confiscated Loyalist property to its owners or at least compensate these loyal refugees for their losses. Far from regaining their property, most Loyalists still suffered harassment, ridicule, physical harm, and sometimes even death when attempting to collect their property in the former American colonies after the war. These violations represented breaches of Articles IV, V, and VI of the Treaty of Paris. Burt, United States, 95–98; Ritcheson, Aftermath of Revolution, 59–69,80–87. The entire Treaty of Paris, including a nonratified article of the treaty, is found in Bemis, Diplomacy of the American Revolution, 259–64.

Willig, Timothy D. Restoring the Chain of Friendship. British Policy and the Indians of the Great Lakes, 1783–1815. University of Nebraska Press, 2008. 275; notes to pages 13–15.

This resulted in tensions (and reciprocal reneging) not settled until the ‘Jay Treaty’ of 1794. Apart from the ‘Hot’ War of 1812, it almost went hot again on other occasions, not least in the aforesaid 1783–94 period:

• In 1793, revolutionary France’s ambassador to the US, Edmond-Charles Genêt, was able to commission four privateers in South Carolina to attack British ships and recruit American militias to attack British and allied Spanish territory. A significant part of the American public favoured allying with revolutionary France and resuming war with Britain; however, a faction led by Alexander Hamilton opposed this and President Washington proclaimed US neutrality in April, a policy contested by the faction led by Thomas Jefferson, publicly in a series of pseudonymous open letters. After falling out of favour with the Jacobin regime, Genêt settled in the US and became a citizen.

• The Arbuthnot and Ambrister affair in 1818:

[General, later President, Andrew] Jackson executed two British subjects on Spanish land in the absence of authorization or precedent, despite the fact that the United States was technically at peace with both Great Britain and Spain at the time.

Outrage was expressed in both press and Parliament:

The London press was no less angry over the execution and there were widespread demands in Britain that action be taken. In addition to newspaper attacks, there were also a number of bitter debates in Parliament about the “unwarranted executions.”

• Supporting Canadian rebels 1837–39, including invading Canada (‘Invasion of Prescott’) in 1838, leading to the Battle of the Windmill, and raiding from US soil (‘Patriot War’).

• ‘Lyman Cutlar touches off Pig War between U.S. and Great Britain on June 15, 1859.’:

The shooting ignites a long-simmering dispute between the United States and Great Britain over ownership of the San Juans, as both nations send troops to occupy the island. The hostile forces face each other for more than 10 years from camps on opposite ends of the island before the dispute is settled[.]

Although British officials continued to advocate a policy of neutrality, they did order troops to Canada and additional ships to the Western Atlantic. Neither the United States nor Great Britain wanted war, but it was clear that, at best, the Trent incident had sparked a major diplomatic disagreement and, at worst, appeared to have pushed Great Britain and the United States toward the potential for armed conflict.

• In 1862, Anglo–American relations were such that General Sir James Shaw Kennedy, distinguished veteran of the Napoleonic Campaigns, saw fit to pen ‘Scheme for the Defence of Canada’, a plan to defend against an attack from the ‘Federal States’ and which he appended to his famous Notes on the Battle of Waterloo (London, 1865; 181–199), writing (183):

One of three states of things may result from what was the United States of North America: the Union may be restored—the Confederates and Federalists may separate and continue to have each much the same territory as at present—or the Confederates may succeed in separating themselves from the Federalists, and the latter split into further subdivisions. Now it is only in the latter case that Canada would be free from the liability of being attacked by the large force [200,000 men] supposed; and hence the necessity for placing that country in a permanent state of security; … .

• The Alabama claims dispute 1868–72, where the US demanded compensation for damage wrought by privately British-built Confederate commerce raiders during the US Civil War (1861–65), primarily CSS Alabama.

• ‘Venezuela Boundary Dispute, 1895–1899’:

[I]n December 1895, President Grover Cleveland asked Congress for authorization to appoint a boundary commission, proposing that the commission’s findings be enforced “by every means.” Congress passed the measure unanimously and talk of war with Great Britain began to circulate in the U.S. press.

For further reading, see: Tuffnell, S. (2011) “Uncle Sam is to be sacrificed”: Anglophobia in late nineteenth-century politics and culture. American Nineteenth Century History. 12(1), 77–99.

Since then, the ‘Special Relationship’ has been rather one-sided, from USG’s shutting Britain out of the Atomic Bomb programme in violation of previous agreements, to refusing to extradite IRA terrorists or shut off IRA funding from NORAID. The Suez stab in the back was a prime example, when USG sided with the Soviets to back an Egyptian dictator over their allies, Britain and France, a mere 3 years after all three countries had fought side by side in Korea and barely ten years after fighting against Germany and Japan, threatening to crash Sterling (and, presumably unknown to us, even contemplating military action against us(*)). Later, USG pressured us to accede to Icelandic demands during the ‘Cod War’, Johnny-Come-Lately Iceland apparently more important to USG than the ally of three wars.

(* See: Kyle, Keith. Suez: Britain’s End of Empire in the Middle East. 1991. I.B. Tauris, 2011. 412; & Calhoun, Daniel F. Hungary and Suez, 1956: An Exploration of Who Makes History. University Press of America, 1991. 381.)

So, in summary, Scruton advocates at least 110 years of Cold War between an independent Scotland and England with at least one Hot War and a few border skirmishes, followed by a ‘special relationship’ where Scotland helps England when perceiving advantage in it, and stabs England in the back when perceiving advantage in that, all the while tolerating and funding anti-English terrorists.

[24] A.C. Grayling tweeted support for the UK’s dissolution in 2017 and 2018 at least. (En passant, Professor of Philosophy A.C. Grayling seems to be the go-to expert on strategic bombing for fellow separatist, Peter Hitchens.)

[25] Regrettably for our Ulster brothers, the defensibility of Ireland is compromised by Partition. Nevertheless, Ulster is ours: we purchased it with the blood of our dead, as they purchased our loyalty with the blood of theirs. Any inconvenience is far outweighed by their contribution—no sooner does one tot up the costs of the Ulster partnership and begin cynically wondering if it is time to end it, than one reads a story like this, and one can only stamp the bill: ‘Redeemed in full’.